The Village of Flagstaff, which took its name from the flagpole erected by Benedict Arnold’s men during his famous march, drew its first permanent settlers in the early 1800s. Settlers came for the soil of the Dead River floodplain, the power available from the outlet of the naturally-occurring Flagstaff Pond, and especially the area’s rich timber resources (Burnell and Wing 2010).

In the 1940s, Myles Standish (a descendent of the pilgrim of the same name) build Flagstaff’s grist and sawmills, which were powered by a small dam on the outlet known as the Mill Stream (Lamb 2009). During the same period, the area around Flagstaff was also being settled, including Dead River Plantation (Burnell and Wing 2010).

The fate of the Dead River Valley’s lost towns was a product of the era of hydroelectric power in Maine. Walter Wyman and his company Central Maine Power, began buying up small local power companies in the early 20th century, consolidating Maine’s electricity production. Central Maine Power Company went on to build and operate a series of hydroelectric dams in Maine – but to do this, Wyman wanted to build a dam that would control the flow of the Kennebec River (Judd n.d.).

Originally, Wyman planned this dam at The Forks, where the Dead River meets the Kennebec. Wyman met with opposition by legislator Percival Baxter, who would later become governor of Maine. Ultimately the Maine legislature chose to approve Wyman’s plan on the condition that he lease the state-owned lands his company would be flooding (Maine Public Broadcasting 2000). Because of the cost of leasing the land, Wyman looked toward an alternative – which included the construction of a dam at Long Falls on the Dead River, sealing the fate of two small towns in the Dead River Valley (Burnell and Wing 2010).

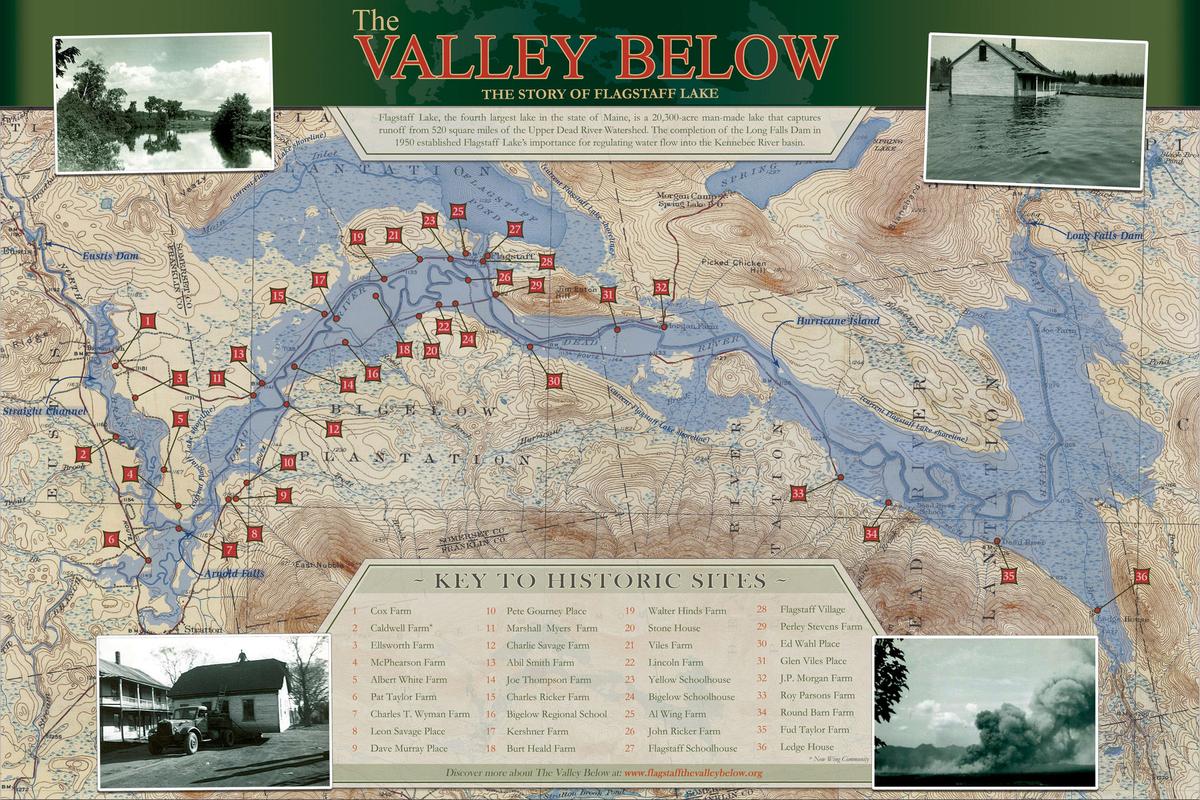

In 1930, Central Maine Power began purchasing the land that would be flooded. In 1948 and 1949, the company hired crews to clear the flowage area. During the summer of 1949, smoke engulfed Flagstaff as the crews burned the brush that remained. A year after that, the Long Falls Dam had been completed, its gates shut, and the town of Flagstaff and Dead River was underwater. Some of the town structures, like the schoolhouse, were razed; others were removed out of the path of the diverted Dead River; some, because their owners had not settled on compensation with Central Maine Power Company, remained standing as the floodwaters rose in Flagstaff (Maine Public Broadcasting 2000).

Today, the reservoir covers what was once the village of Flagstaff is Flagstaff Lake, Maine’s largest man-made lake.

The people of the flooded towns relocated. Central Maine Power Company bought their properties, selling some houses back to families so they could move to higher ground (Maine Public Broadcasting 2000). Some former Flagstaff residents moved to neighbor towns like Eustis, which is home to Flagstaff’s and Dead Rivers relocated cemeteries as well as Flagstaff Memorial Chapel.

In 1999, fifty years after the Dead River was diverted by the Long Falls Dam, the Flagstaff Memorial Chapel Association published “There Was A Land: Memories of Flagstaff, Dead River, and Bigelow”. The book includes stories of the lost towns from its residents and friends (Flagstaff Memorial Chapel Association 2001).

The villages of Flagstaff and Dead River were causalities of progress. Interviews and writings by former residents convey the loss felt by all who lived in the Dead River Valley. Again and again, residents also described a sense of inevitability as demand for electricity increased and outsiders touted the benefits of harnessing the Dead and Kennebec Rivers. Maine’s industrial and individual power customers moved forward in people of Flagstaff and Dead River.

Story courtesy of the Dead River Area Historical Society.